KNOW YOUR 1980s DENVER BRONCOS

KNOW YOUR 1980s DENVER BRONCOS

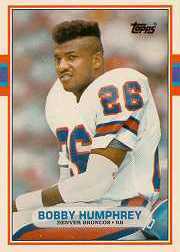

This week, the third in a series of team-leading runners, #26, Bobby Humphrey.

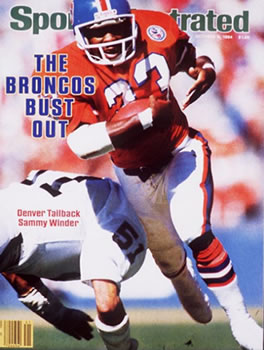

Looking to replace the retiring Tony Dorsett and the aging Sammy Winder, the Broncos selected Bobby in the 1989 Supplemental Draft. He had two terrific seasons for the Broncos, gaining over 1100 yards both years, making one Pro Bowl, and helping the team reach a Super Bowl. Denver seemed to have found the star runner they had long sought to complement John Elway, and the future looked bright. Of course, Bobby knew how important he was to Coach Reeves and the team, so he sadly decided to leverage his value by holding out in an attempt to get a new contract. Most holdout situations magically resolve around the time that either the brutal training camp schedule ends or the paying schedule of actual games begins. But Bobby sat out for most of the 1991 season, waiting in vain for the team to accept his demands, while the Broncos stuck to their team policy of not negotiating with holdouts. Realizing the Broncos were doing well even without him, Bobby relented and returned for the final few games of the season, but did not play a major role for the team. He was traded to the Miami Dolphins before the following season, where he played only sparingly for a year.

Looking to replace the retiring Tony Dorsett and the aging Sammy Winder, the Broncos selected Bobby in the 1989 Supplemental Draft. He had two terrific seasons for the Broncos, gaining over 1100 yards both years, making one Pro Bowl, and helping the team reach a Super Bowl. Denver seemed to have found the star runner they had long sought to complement John Elway, and the future looked bright. Of course, Bobby knew how important he was to Coach Reeves and the team, so he sadly decided to leverage his value by holding out in an attempt to get a new contract. Most holdout situations magically resolve around the time that either the brutal training camp schedule ends or the paying schedule of actual games begins. But Bobby sat out for most of the 1991 season, waiting in vain for the team to accept his demands, while the Broncos stuck to their team policy of not negotiating with holdouts. Realizing the Broncos were doing well even without him, Bobby relented and returned for the final few games of the season, but did not play a major role for the team. He was traded to the Miami Dolphins before the following season, where he played only sparingly for a year.

He played in Super Bowl XXIV, in which the Broncos were pummeled by the San Francisco 49ers 55-10. He did his part to earn those 10 points, though, leading the team in both rushing and receiving yards.

So what makes Bobby Humphrey so awesome? Well, tough call. His hair, for one thing. He was also probably the most talented running back the Broncos had during the 1980s (if one considers only the worn-down Broncos version of Tony Dorsett). But talent only goes so far. By contrast, Sammy Winder contributed a great deal more to the team’s successes and should be more fondly remembered. Bobby’s career derailed before he really had a chance to establish himself. Bobby was a good player that could have had a major role on a powerful team for years. Instead, his disastrous decision to hold out before he’d really earned his place pretty much ruined his football career. He never regained his stride or the respect of team management. A 2006 Denver Post article called his decision “the most infamous holdout in Broncos history.” I guess that’s an accomplishment. Bobby seemed regretful of his actions in the article, noting that it was a decision he made in youth and inexperience that didn’t pan out well, and that he should have handled himself better during the negotiations.

Since leaving the NFL, Bobby has spent time as an Arena League coach and currently works for a concrete dealer in his home state of Alabama. His son is a notable football prospect that will attend the University of Arkansas starting this fall.